Apartheid ended 20 years ago, so why is Cape Town still 'a paradise for the few'?

The South African city is World Design Capital 2014, yet residents of Khayelitsha township live in cramped, unhygienic conditions. The need for long-promised urban reform is urgent

An 'active box' – part community centre, part safe haven – rises above the market of Cape Town's Khayelitsha township. Photograph: Joy McKinney

Sitting on a salvaged sofa in the centre of her small tin shack, Nomfusi Panyaza looks increasingly worried, as heavy clouds gather in the sky outside. “When it rains, the public toilets overflow into my living room,” she says. “Water comes in through the ceiling and the electricity stops working.”

Outside her makeshift home in the sprawling township of Khayelitsha, on the eastern edge of Cape Town, barefoot children play on the banks of an open sewer, while cows roam next to an overflowing rubbish heap. Panyaza shares this tiny cabin with her two daughters and four grandchildren, a family of seven with two beds between them. “We can't sleep at night because of the smell,” she says, speaking in Xhosa, a language peppered with clicks that echo the droplets beginning to drum on the corrugated metal roof. “I'm worried that the children are always getting sick.”

Twenty minutes' drive to the west, the seventh course is being served at a banquet of assembled journalists, here to celebrate Cape Town's title of World Design Capital 2014 on the terrace of a cliff-top villa. An infinity pool projects out towards the Atlantic horizon, as the setting sun casts a golden glow across the villa's seamless planes, their surfaces sparkling with Namibian diamond dust mixed into the white concrete. Guests admire how the bath tub is carved from a solid block of marble, while security guards keep watch in front of a defensive ha-ha down below, ringed by an electric fence.

Twenty minutes' drive to the west, the seventh course is being served at a banquet of assembled journalists, here to celebrate Cape Town's title of World Design Capital 2014 on the terrace of a cliff-top villa. An infinity pool projects out towards the Atlantic horizon, as the setting sun casts a golden glow across the villa's seamless planes, their surfaces sparkling with Namibian diamond dust mixed into the white concrete. Guests admire how the bath tub is carved from a solid block of marble, while security guards keep watch in front of a defensive ha-ha down below, ringed by an electric fence.

Apartheid may have ended 20 years ago, but here in Cape Town the sense of apartness remains as strong as ever. After decades of enforced segregation, the feeling of division is permanently carved into the city's urban form, the physical legacy of a plan that was calculatedly designed to separate poor blacks from rich whites.

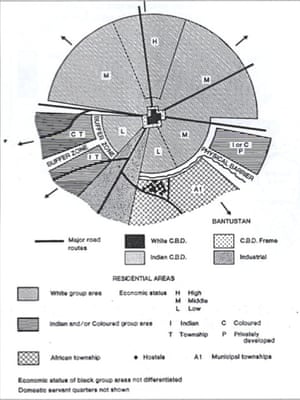

“The social engineering of apartheid came down to a very successful model of spatial engineering,” says Edgar Pieterse, director of the African Centre for Citiesat the University of Cape Town. Tracing his fingers over a map of the city in his office, he explains how both natural landscape features and manmade infrastructure were employed as physical barriers to keep the different racial communities as isolated as possible.

“Cape Town was conceived with a white-only centre, surrounded by contained settlements for the black and coloured labour forces to the east, each hemmed in by highways and rail lines, rivers and valleys, and separated from the affluent white suburbs by protective buffer zones of scrubland,” he says.

From 1948, when the apartheid administration began, South Africa's cities adopted the strict zoning principles of modernist urban planning, taking inspiration from Ebenezer Howard's garden city movement and Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse, only repurposing their dogma of functional segregation towards racial ends.

The process of relocating Africans to peripheral townships would not only cleanse the white centres, but create new blank sites, sterilised of any reference to indigenous culture and tradition. These modern, orderly settlements, it was thought, would mould the black labour force into an orderly, submissive underclass. With security and control, rather than health and happiness, as the chief motivations, the townships were designed along the lines of military barracks. Streets of grim “matchbox houses” were laid out in strict grids and surrounded by a fence, with only two or three points of entry, allowing the police to seal off entire neighbourhoods with minimal effort.

Driving along the main road from the airport to the city, through the barren and windswept Cape Flats that roll out to the east, this militaristic planning is still very much in evidence. Thirty-metre high lighting masts loom above the homes at regular intervals, with floodlights glaring down all night over the wide streets, so the area can be easily surveyed from a helicopter. Housing is set back at least 60 metres from the road, a dimension, like the lighting masts' height, that is governed by the distance you can throw a stone.

During the years running up to the 2010 Fifa World Cup, this drive into town was spruced up. Either side of the motorway, as part of the N2 Gateway Project, shanty-town shacks have been replaced with neat brick and render houses, each topped with a bright orange pan-tile roof. But look beyond this thin crust of decent homes – a block-deep Potemkin facade of regeneration – and a sea of jumbled shacks continues to stretch endlessly into the distance.

For all the city's attempts at a cosmetic makeover, which was roundly condemned by international NGOs for the accompanying programme of forced evictions, this route into town still provides a striking object lesson in the power of apartheid planning. Beyond the townships, which appear increasingly titivated the closer towards the city you progress, stands the site of a former power station. Then there is a sewage treatment plant, followed by the neatly manicured mounds of a golf course, the bend of a river, a deep valley and a tangle of intersecting roads. The black communities were separated from whites not only by distance, but by as many physical obstacles as possible, the more polluting the better.

“Points of contact invariably produce friction and friction generates heat and may lead to a conflagration,” declared South Africa's minister of the interior, Dr T E Tonges, in 1950, when he introduced the Group Areas Act, the law that enforced the division of cities into ethnically distinct areas. “It is our duty therefore to reduce these points of contact to the absolute minimum which public opinion is prepared to accept.”

While it saw the savage separation of mixed-race families, and the wholesale demolition of non-white areas – such as Cape Town's vibrant District Six, which still stands as an overgrown wasteland in the centre of town – the Act only cemented a tendency of white settlers retreating behind barriers that had been present in the Cape for over 300 years.

In the mid-17th century Jan van Riebeeck, leader of the first Europeans to settle in South Africa, proposed the typically Dutch solution of digging a canal across the Cape Peninsular to separate the white paradise as a self-contained island, cut off from the rest of “darkest Africa”. Unable to realise this ambitious project, he instead decided to plant a bitter almond hedge to keep the “black stinking dogs” out of his settlement, accompanied by brambles and thorny bushes designed to ward off this “savage set, living without conscience”.

Systematic segregation continued into the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the British colonial government forcibly resettled black communities under the pretence of curbing an outbreak of the bubonic plague. Further acts of parliament prevented the acquisition of land by “natives” and limited movement by a draconian system of internal passports, preceding apartheid legislation by 25 years. The Urban Areas Act of 1923 ordered the removal of Africans from desirable city centres to “locations”, one of the first of which in Cape Town, Langa (which ironically means “sun”), was sited right next to the sewage works.

Since 1994, when the African National Congress came to power and apartheid was finally ended, South Africa has struggled to even begin to undo these centuries of divisive planning. In some cases, misguided initiatives have only served to strengthen it.

“The time to build is upon us,” declared Nelson Mandela in his inaugural speech as president, launching what would become one of the biggest state housing development projects in the world. The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) has seen over 3.6 million new homes built across the country since then, provided free of charge to those on monthly incomes of less than 3,500 rand (£200). But these have come with their own problems: despite the improvements in individual living conditions, there is a growing realisation that the RDP housing programme has reinforced apartheid era segregation, continuing to consign the poor to ghettos at the furthest edges of the city. Building is one thing, but time for planning might have been helpful first.

Walking past these identical single-story sheds, marshalled into grim repetitive rows (not nicknamed dog kennels for nothing), it is often hard to distinguish the RDP buildings from the hated matchbox houses built in the townships under apartheid. They have been thrown up quickly and cheaply, and many have already come crumbling down, while their dreary layout reinforces the sense of living in an open-air prison. They also have the tendency to spawn their own informal buildings next door, fuelling the development of choked streets of unplanned shacks.

“When many people finally get an RDP house, often after 10-15 years of waiting, they realise it makes more economic sense to build a shack in the backyard for themselves and sell the house,” says Pieterse. “They sell them illegally for about 40,000 rand (£2,300), a third of what it costs the state the build them, and then they can use this cash to set up a business from the shack. It makes a lot more economic sense than living in the RDP house, where you're not allowed to trade.” (Wait, WHAT!?)

Wandering the potholed streets of Khayelitsha today provides such a tale of two cities, where the planned and unplanned jostle for position. On one side of the road stands an orderly row of RDP houses, their gable ends neatly rendered in pastel shades of peach and tangerine. But turn the corner and a jumble of shacks spills out behind, an energetic collage of corrugated sheeting held up with salvaged fenceposts. There are gates cleverly constructed from plastic crates and mail boxes fashioned from a oil cans, all liberally doused in bright blues and pinks, greens and yellows, tying each assemblage into a carefully crafted home.

It is easy to romanticise this vibrant, makeshift culture – indeed township tours regularly shuttle groups of tourists out here for a dose of shanty-town chic – but the reality of life inside belies the picturesque surface and beaming welcome. Over a quarter of households have no access to electricity, while each outdoor tap is shared between around twenty families, each toilet between ten.

Every plot, whether from the RDP programme or dating from when the township was first laid out in 1984, is now often home to four or six other dwellings, each sharing the minimal amount of electricity provided to the original legal household.

“Sometimes my neighbours just turn off the power and hold me to ransom,” says Panyaza, staring at a blank television in front of her sofa, the principal possession around which the rest of her small home is organised. In one corner of the room, a gas canister and pile of pots indicate the kitchen area, while behind a flimsy screen of fibreboard panels are the two bedrooms, each no bigger than a mattress. Possessions are piled in boxes and suitcases, as if they could be ready to leave at a moment's notice.

“We've been forgotten,” says Panyaza, who built her home ten years ago, when she first moved here with her family from the Eastern Cape in search of work in the city. They have been on waiting list for an RDP house ever since.

Their story is shared by thousands of families who arrive here each year from the poorer eastern province, an influx that sees around 10,000 new shacks built annually in Khayelitsha alone. Originally planned as a community of 200,000, the population now numbers around one million, half of whom live in informal housing, making it one of the biggest and fastest growing townships in the country.

It is a speed of growth and level poverty, with over 50% unemployment, that has also brought Khayelitsha one of the highest crime rates in the country, and a reputation as a place ruled by gang violence. Police say they deal with an average of four murders a weekend, while the local hospital is overrun with stab-wound and gunshot victims every night.

“It's so bad in some areas that the police won't even go in,” says Sonwabile Swartbooi of the Social Justice Coalition, a local community NGO focused on improving safety and sanitation in the area. “Children are often too scared to walk to school in case they get caught in crossfire.”

With a Commission of Inquiry under way into alleged police inefficiency in Khayelitsha, there is little confidence in the justice system, and vigilante mobs sometimes take matters into their own hands. “The mobs punish suspected criminals with 'necklacing',” says Swartbooi. “They chase them down and beat them, then trap them inside petrol-filled tyres and set them on fire.”

It is within this fraught context that German urban designer Michael Krause has been working since 2008 on a series of projects that aim to tackle violence through simple improvements to the township's streets and spaces.

“Our approach is to positively occupy places that are perceived to be dangerous,” he says, standing outside a construction site, where local workmen clamber atop a structure of bright red shipping containers and rendered sand-bag walls, soon to be a new community centre. Across a dusty lot sits a heap of scrap metal, patrolled by a couple of emaciated dogs, while a toddler squats in the street, examining the sole of a discarded shoe.

“This used to be the site of an illegal chop shop,” says Krause. “Hijacked cars would be brought here to be dismantled and sold on. The community wasn't strong enough to stand up to the criminal elements, so we took them through a leadership process to give them the strength to do it themselves. The choice was either build a community centre, or be ruled by criminals. That's sustainability.”

The centre is one of a number of “active boxes” that have been built in the area over the last few years, conceived as hubs of 24/7 activity – part community centre, part safe haven, manned by volunteers from the nascent neighbourhood watch initiative. Each has a multi-purpose room, used for meetings and youth groups, along with a caretaker's flat, as well as spaces for shops and start-up businesses or a creche. Positioned every 500 metres along a route through the township, with their slender red watchtowers rising above the rambling rooftops, the active boxes now stand like a line of proud church spires.

“They are like the blue cheese in a gorgonzola,” says Krause, walking through a huddle of market stalls, where chickens are being plucked and corn is roasting on smoking coals. “They are safe nodes, connected by paths that thread their way through the township, from the market to the station to the schools and so on, defining well-lit routes monitored by passive surveillance.”

Leading the Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading programme, an initiative jointly funded by the provincial government and the German Development Bank, Krause and his team spent months working with the community to map crime hotspots and work out the safer, regularly used routes through the area. The active boxes are accompanied by a package of public realm improvements, from street lighting to new paving and recreation spaces, along with “active citizenship” programmes, empowering residents to drive these projects forward themselves.

It is a community-led approach that contrasts with the blunt hand of previous top-down interventions, such as the Khayelitsha shopping mall, a cluster of out-of-town retail sheds airlifted into the township in 2005, but hopelessly cut-off, sited the wrong side of a railway line. “They call it our new town centre, but it's in totally the wrong place,” says one local resident, walking back across the bridge over the tracks. “It may be shiny and new, but it doesn't feel safe to go there.”

Just a short way to the south, in the neighbourhood of Harare, the biggest VPUU project shows how things can be done differently. In the centre of the area now stands a tarmac square, lined either side with new red-brick buildings, carefully designed to frame this new civic space with active frontages. There is a big new library to one side (which now claims to be the busiest public library in Cape Town) next to a building called the Love Life youth centre. Lining the other edge of the square is a neat row of live-work units, with what looks like the beginnings of a high street, complete with a hair salon, internet cafe, co-op bank, TV repair shop, security company and a restaurant – all things that would have been unimaginable 20 years ago, when independent business was outlawed in the townships.

“It's completely changed the feeling of the area,” says 18-year old Bongi Qwesha, walking through the square on her way back from school. “It wouldn't have felt safe to hang around here a few years ago, but now we all come here after school to meet in the square and go on the internet.”

Krause says there has been a 33% reduction in the murder rate in Harare since the programme began in 2005, along with an increase in the general perception of safety (if only from 2 to 2.8 on a 5-step scale), figures which have seen the programme already expanded to other townships around the city.

But it hasn't come without a fight. Krause's team, and those who rent the new business units, face regular intimidation from the gangs, whose iron grip over the local economy is being slowly displaced by these initiatives. “That's why we never just wade in and move people on,” says Krause. “It's a very long and intense process of giving the community the confidence to do it for themselves. The city could just continue to airlift these spanking new facilities on to empty sites around the township, but when we do it, we take the time to make sure it's in the right place. It can take up to two years, just to assemble the land for a small project.”

The VPUU's work has yet to reach the peripheral lanes where Panyaza and her family reside, but she has heard that new flushing pubic toilets are on their way, to replace the chemical portaloos – prone to being locked from the outside and tipped over while someone is inside. “If they stop overflowing, we'll sleep better at night,” she says. “But I'm not holding my breath.”

Back in the centre of Cape Town, the World Design Capital entourage returns from the Veuve Clicquot Masters Polo tournament, “South Africa's most exclusive luxury lifestyle event,” where celebrities mingle with designers in the impossibly picturesque surroundings of the Val de Vie estate, in the rolling winelands to the north of the city. High on a cliff above the city, a cocktail reception awaits at another hilltop mansion, where a manicured lawn commands panoramic views across the bay – and from where guests notice billowing clouds of smoke rising in the distance. “Don't worry,” assures their guide, reaching for another glass of champagne. “It's probably just a fire in one of the townships.”

Following Torino, Seoul and Helsinki, Cape Town is the fourth city to be awarded the title of World Design Capital, an accolade bestowed by the Montreal-based International Council for Societies of Industrial Design, which charges a hefty fee to honour a different city with its logo each year. Cape Town has pumped around £3m of public money into its year of design, but it's hard to tell quite where all the cash has gone. There are craft fairs aplenty, showcasing fine ceramics and bespoke furniture, and open studios demonstrating bronze casting and elaborate taxidermy, but most of the funds appear to have been directed at a launch event in London, a New Year's Eve party, a gala dinner and a weekend conference. As a result, many of Cape Town's more established designers and architects have decided to boycott the bonanza.

“I am offended that the word 'design' can be used so loosely, without any consideration for the damage it is doing,” says architect Jo Noero, who has built a body of work across the country over the last 30 years that is deeply embedded in serving the urgent needs of its poorest communities. From schools and community centres, to low-cost housing designed to be partially self-built and adapted by residents, his buildings are made “with the same integrity in the townships as they would have anywhere else,” he says. “Only that way will we ever begin to dismantle the idea of there being two different worlds in South Africa. Buildings must be designed to engage the enthusiasm and creativity of people – that's the only way a tradition of fine building will develop.”

He says that apartheid utterly destroyed the capacity of people to think about upgrading their own homes, and the reconstruction and development programme programme is only doing the same. “The government is still very paternalistic, so people expect it will provide everything,” he adds. “And they still fear that the more freedom you give people, the less easy it is to control them.

“In South Africa there is a horrible lack of imagination about the future. There are grand plans to build whole new satellite cities outside Cape Town, but they're following the same model of putting the poorest people furthest away. It seems like we're just repeating all the mistakes of the past.”

A few streets away, Noero's former partner, Heinrich Wolff, sits at a desk surrounded by a plethora of models of schools and housing projects, as well as a scheme for a dramatic transformation of a dockside warehouse into a new public-facing “innovation hub” for the university.

“We have massive spatial injustices in our city and we've just been sitting and staring at it for the last 20 years,” he says. “When Mandela came to power we had an incredible moment of change. Optimism gripped us all about a future that would happen – through ongoing transformation, not revolution. We are still busy with that project, but there is now a real urgency.”

He says the voices calling for immediate change are fast growing in strength and volume, with radical groups like Julius Malema's Economic Freedom Fighters surging in popularity, as more and more grow disaffected with the ruling ANC. The incendiary red beret-wearing politician, who fires up frenzied crowds with his song “Kill the Boer” at township rallies, promising to unleash a reign of violent retribution, is what keeps white South Africans awake at night.

“Cape Town is a paradise for the minority, but I could hope for a city where everyone has access to the same opportunities that I have,” says Wolff. “Mandela may have postponed revolution – but for how much longer is the question.”

No comments:

Post a Comment